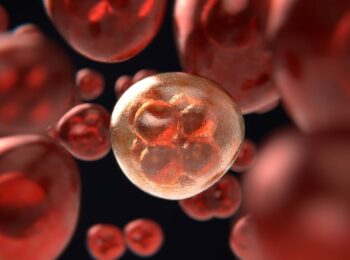

An international research team has found a conceivable way to treat toxoplasma infections, the parasite that typically infects cats and can infect us too.

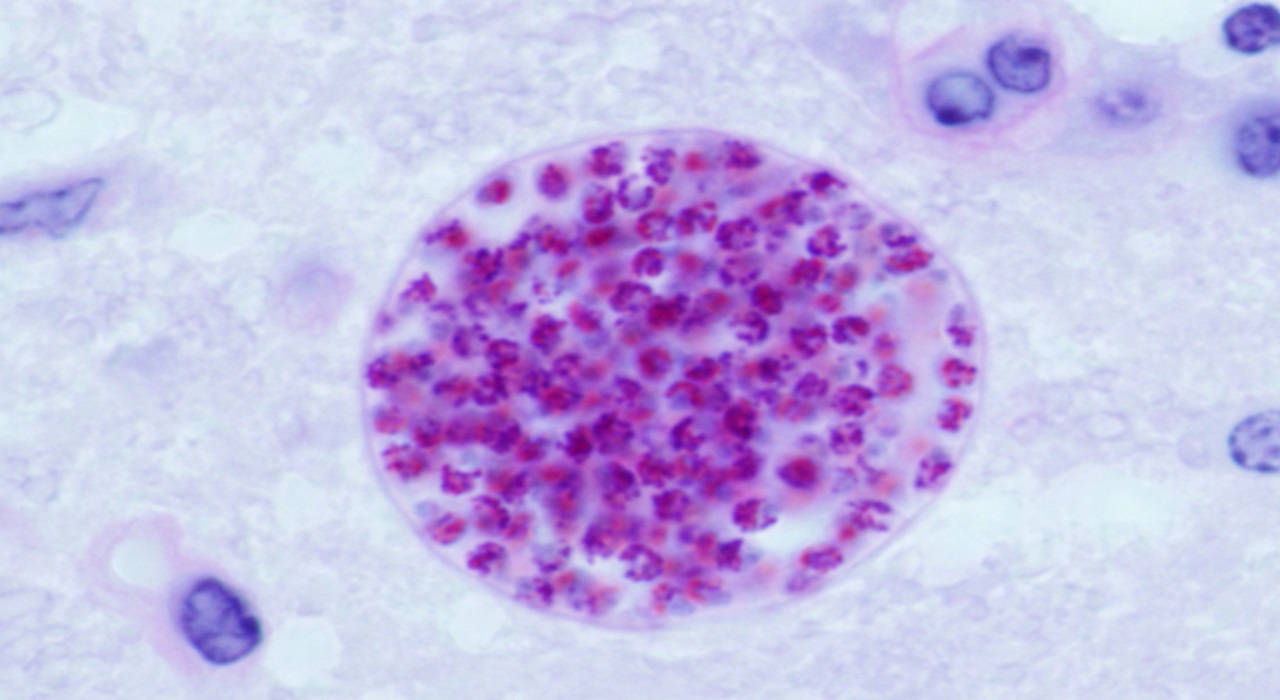

The Toxoplasma gondii parasite can jump to humans who are in close contact with infected cats or by eating infected meat. The parasite then passes through the stomach, intestines, the bloodstream and into the brain. There it forms small cysts where it grows, then hibernates and remains in the brain throughout the lifetime of its host.

The parasite infection is very common, and in fact, infections are most common in developed countries as serological studies (A. L. Sutterland et al. have shown, an estimated 30 to 50 percent of the global population has been exposed to and may be chronically infected, although infection rates differ significantly from country to country.

Most people remain unaffected by the parasite, although, studies have shown that subtle behavioral or personality changes may occur in infected humans (Jaroslav Flegr). The parasite has recently been associated with a number of neurological disorders, particularly schizophrenia (Joanne P. Webster et al) and bipolar disorder (de Barros JL et al.).

There are some certain groups people for which the Toxoplasma infection can become dangerous. One such risk group is pregnant women since the parasite can be dangerous to the fetus. Therefore, pregnant women are advised to not change or handle cat litter boxes. Another risk group comprises those with a compromised immune system, for whom toxoplasmic infection can actually be fatal.

Today, there is no treatment for the toxoplasma parasite. Partly due to a poor understanding of the essential pathways that maintain long-term infection. But a new study published in the Journal Nature may just change that.

When the parasite reaches the brain of its host, it goes into a kind hibernation mode and lowers its metabolism to a very low level. Now, researchers at the University of Michigan have discovered that the parasite is dependent on a certain enzyme in order to not starve to death.

This enzyme, called cathepsin protease, breaks down and reuses cellular materials that the parasite then uses as energy during its long hibernation. But when the researchers inhibited the enzyme by interfering on a genetic level and also using a drug, the parasite died.

These findings suggest an unanticipated function for parasite lysosomal degradation in chronic infection and identify an intrinsic role for autophagy in the T. gondii parasite and its close relatives.

This work also identifies a key element of Toxoplasma persistence and suggests that VAC proteolysis is a prospective target for pharmacological development.

– The researchers write.

This could prove an important breakthrough, but the researchers point out that the particular enzyme can only be inhibited in an in-vitro lab setting as of now. Since the substance cannot pass the blood-brain barrier and therefore does not reach the parasites inside the brain in a live host.

The researchers need to find a similar molecule, or carrier molecule, that enables it to pass the barrier and kill the parasite.

Reference:

Manlio Di Cristina et al., 2017. Toxoplasma depends on lysosomal consumption of autophagosomes for persistent infection. Nature Microbiology. DOI: 10.1038 / nmicrobiol.2017.96