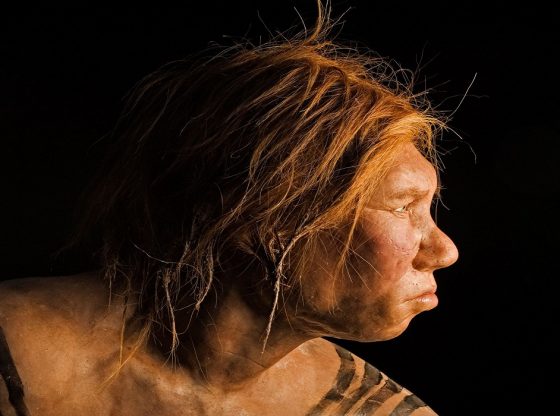

Neanderthals are our cousins from the past, they were slightly shorter in height but probably stronger. In addition, they had some very distinct facial features. New research shows that their noses might have been better than ours.

They are often depicted with powerful muscles, bushy eyebrows, big noses and a coarse jaw. But scientists have long been asking: did their distinctive facial features have an evolutionary purpose?

Now paleontologists and biologists have come up with an answer. Their research shows that the powerful jawbones of the Neanderthals probably did not endow them with a stronger bite as it has been theorized – but their noses could have been specially designed to cope with colder climates.

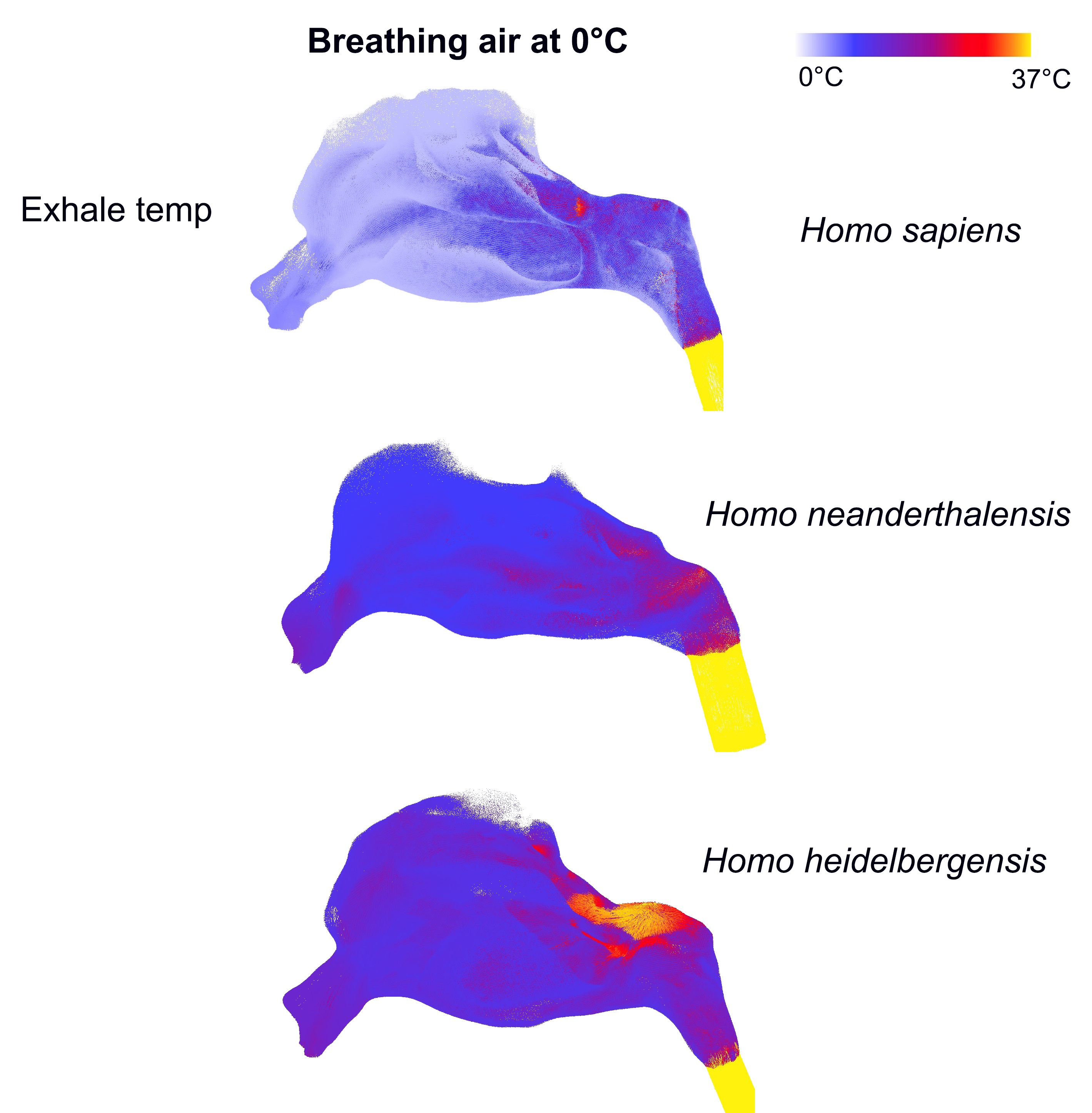

To investigate the evolutionary function of the neanderthal’s facial features, the researchers compared fossils from three different human species. Then, using 3D technology and special computer programs, they could easily see what anatomical differences the skulls had.

In total, eleven bones were used from modern humans, three from Neanderthals and a skull from the prehistoric man, Homo Heidelbergensis. The researchers first examined whether the new models showed a correlation with large jaws of the Neanderthals and a stronger biting force, it didn’t.

On the other hand, the models may point to that the Neanderthal nose, or more specifically the nasal cavity, were adapted to convert large amounts of cold and dry air. And maybe they were twice as good at breathing compared to us.

The Neanderthals seem to have been adapted to a cold climate. And the ability to breathe in an energy efficient manner was definitely better suited to Europe’s climate than modern people are.

Reference:

Stephen Wroe, William C. H. Parr, Justin A. Ledogar et al. Computer simulations show that Neanderthal facial morphology represents adaptation to cold and high energy demands, but not heavy biting DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2018.0085