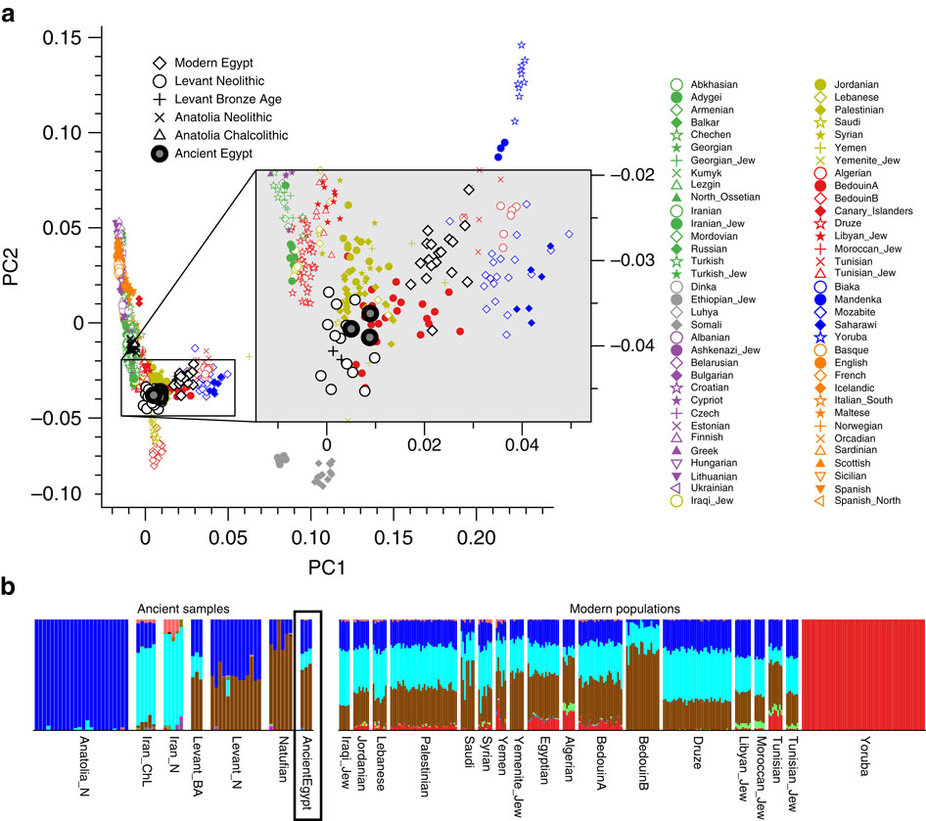

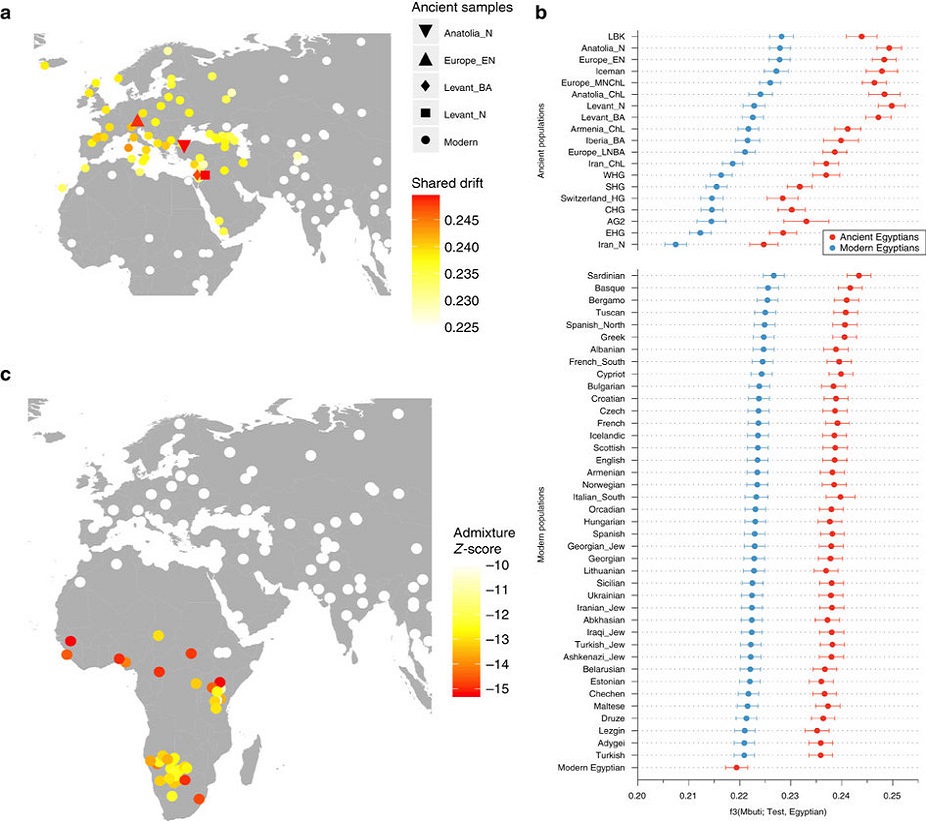

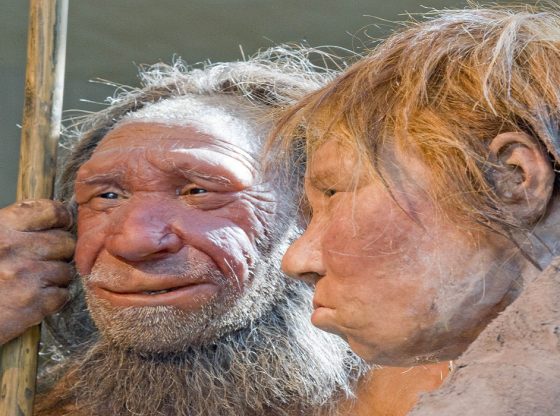

For the first time, researchers have analyzed DNA from Ancient Egyptian mummies, then compared the DNA to that of today’s Egyptians. The ancient Egyptians seem to primarily have genetic links to the Levant and no genes from sub-Saharan Africa as is the case for today’s Egyptians.

The new genetic analysis of the mummies shows something surprisingly different in comparison with today’s Egyptian population. The ancient Egyptians, whose remains are preserved as mummies, originate to the greatest extent from the Levant, from the countries around the eastern Mediterranean and specifically Anatolia in modern day Turkey.

1,300 years of ancient Egyptian history

Scientists looked at DNA from 151 mummified Egyptians excavated in the early 20th century, radiocarbon dating shows that they were entombed 1388 BCE to 426 CE. These 1,300 years of ancient Egyptian history includes many foreign conquests, Egypt’s incorporation into the Hellenistic world and then the Roman Empire.

The new study is an international collaboration between different researchers but led by the University of Tubing and the Max Planck Institute in Germany. They used next-generation sequencing methods perfected by the Max Planck Insititute – a spearhead in genetic research – to read stretches of any DNA present in a sample and fish out those that resembled human DNA.

The mummies were mostly from the archaeological site of Abusir el-Meleq, situated on the Nile River in what was ancient Middle Egypt. It was a graveyard and a cult place during Egypt’s fifth dynasty.

Mitochondrial DNA

Several previous studies have attempted to study DNA from mummies, but it has been difficult to get well-preserved genetic information. Due to several factors, the temperature and since chemicals used in the actual mummification contributes to the breakdown of DNA.

Previous attempts have aimed to isolate and analyze the DNA contained within the cell nucleus and which maintains the entire human genetic information. However, nuclear DNA only exists in two sets in each cell and can be difficult to find.

Therefore, the researchers chose to instead analyze mitochondrial DNA contained in the mitochondria, i.e., the cellular power stations. There are up to 1,000 copies in each cell that are more often better preserved.

The disadvantage of mitochondrial DNA is that it does not provide an as comprehensive picture as nuclear DNA, but as it is inherited only on the mother’s side, it makes it easy to study family relationships.

Homogeneous DNA

The mitochondrial DNA showed that the Egyptian Egyptians were mainly related to people from the Levant, but also to people from Western Asia and Europe. The mitochondrial DNA was also approximately the same in all mummies during the whole period, and no large amounts of DNA have been added.

The ancient Egyptians, therefore, seems to have been a relatively homogeneous people and did not mix their genes with other populations over the period of 1,300 years. The researchers specifically looked at the event of Alexander the Great conquering Egypt 331 BCE but did not detect any foreign genetic traces from this specific event.

When the researchers compared the DNA to that of modern Egyptians, however, big differences were observed. There is a substantial addition of sub-Saharan genetics in modern day Egyptians, which is not found in any of the prehistoric samples.

Modern Egyptians share eight percent more DNA with African populations than the Egyptians of the past. This indicates that the flow of genes from Africa has increased over the past 1,500 years. Increased mobility and trade on the Nile can be an explanation. The Arab slave trade another.

The scientists note, however, since the mummy DNA was from a single archeological site, their results cannot be generalized to the south or north of Egypt (Upper or Lower Egypt), which may have been more or less affected by foreign conquest.

The study has been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Reference:

Verena J. Schuenemann, Alexander Peltzer, et al. Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods doi:10.1038/ncomms15694