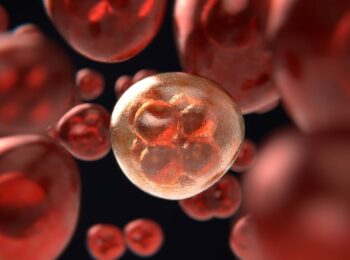

There are only three known species of animals, including humans, that go through menopause. The other two mammals are chimpanzees and killer whales (orcas). Now, new research sheds light on why female orcas go through menopause.

According to a new study by an international research team, the risk is higher that the offspring of older females die if the females continue to have more offspring.

Scientists have previously been able to see that older orca females often play an important role as leaders, which benefits the flock. But the benefits of helping their adult male and female offspring are not the only reason that would explain why female orcas stop having more offspring after a certain age.

New research indicates that menopause is also a result of competition between younger and older females. The offspring’s survival is more important for younger females than for older, since, for the older females, the flock’s survival is also of great importance.

Older females have offspring which in turn have offspring and the older a female becomes, the more the flock becomes her offspring. If an older female orca gets have offspring and then a second or third generation offspring at the same time, this increases the risk of competition in the herd and thus the risk of increased mortality in the flock.

Because older females are more related to the others in the group, this effect is only strengthened with age and a growing flock and much lower for younger females. Having offspring has its own kind of priority for younger females.

The scientists used drones to study the orcas and this ability to monitor the killer whales from above have been crucial to study their unique social interactions and to understand of these animals.

This dynamic relationship among orcas is most certainly an evolutionary advantage. Since the researchers saw that when older and younger orcas reproduce at the same time, the offspring of the older females are almost twice as likely to die.

Therefore, it appears to be evolutionarily more advantageous for the older female orcas invest in helping the flock on a whole and stop having offspring between 30 and 40 years of age, although they can live until they are at least 90 years of age.

The research study was a large collaboration between researchers from the Universities of Exeter, University of Cambridge and University of York, the Center for Whale Research in the United States, Fisheries and Oceans in Canada,

Reference:

Darren P. Croft, Rufus A. Johnstone, Samuel Ellis, et al Reproductive Conflict and the Evolution of Menopause in Killer Whales DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.015