How is the environment around us and microorganisms affected by us staying within a limited space for long durations? NASA researchers have attempted to answer this question in a new study.

Credit: Blachowicz et al Microbiome 2017

Humans must look to outer space within the next century or it will become extinct according to Professor Stephen Hawking. To do this we must overcome a number of problems, including radiation and the psychological aspects of living within a cramped space.

There is another problem with people to living within a very small space for long periods of time: Researchers at NASA have studied what happens to microorganisms such as bacteria and microscopic fungi during these durations.

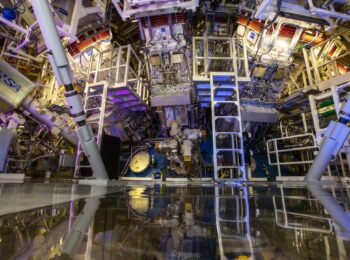

The study included a group recruited students that were to stay within a closed environment for 30 days, intended to simulate the existence of a space station, for example.

Fungi samples were collected from eight sampling locations at four time-points; just before habitation and at 13, 20 and 30 days of habitation. The habitat was cleaned weekly with antibacterial wipes.

The researchers noticed that the living fungus flora changed remarkably. This happened even though no new fungi were allowed in.

Some fungi prospered while others declined. The researchers saw, for example, increasements in fungi (Cladosporium cladosporioides) that could potentially cause infections, asthma or allergy in humans.

The researchers emphasize the necessity to keep an eye on the environment to prevent potential overgrowth of fungi that could potentially harm individuals and propose that new methods need to be developed to maintain and clean the environment.

The study is certainly interesting in the context of future space exploration for what it is intended, but also, relevant for any environments on Earth today where many people live and work.

Reference:

Blachowicz et al.,”Human presence impacts fungal diversity of inflated lunar/Mars analog habitat“, publicerad 11 juli i Microbiome, doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0280-8