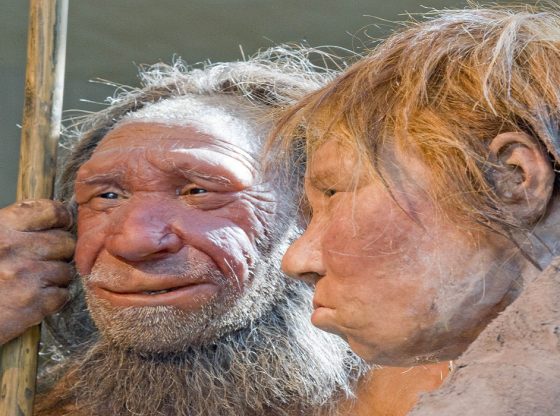

New research indicates that there was no major immigration from the Middle East into the prehistoric Baltics as was the case for the rest of central and western Europe.

The Baltic region in north-central Europe on the eastern edge of the Baltic Sea appears to have a different genetic history than the rest of Europe. The hunter-gatherers living in this region acquired the knowledge of farming and using ceramics by sharing ideas, rather than genes, with other communities.

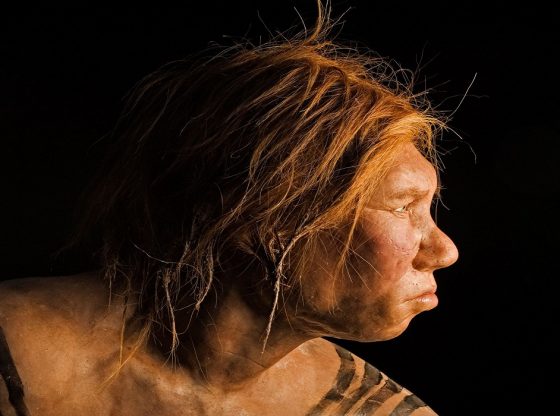

Researchers extracted DNA from individuals that lived between 4,800 and 8,300 years ago, six of which was found in what is now Latvia and two in what is now Ukraine. The researchers were able to map their ancient DNA that spanned the Neolithic period at the dawn of agriculture in Europe.

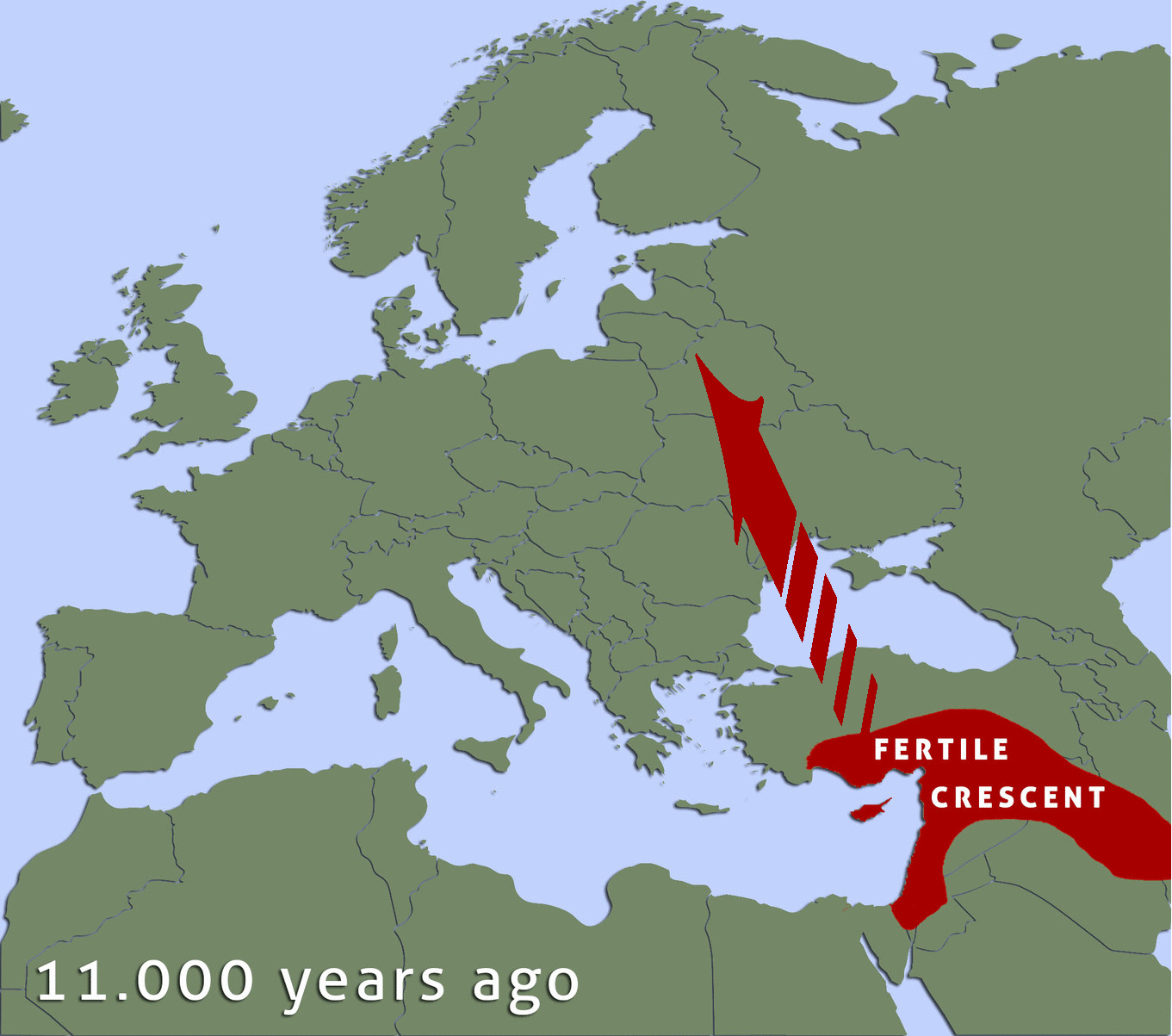

This period was marked by a large migration of people from the Levant (the Near East), bringing with them a settled way of life, based on stationary food production. Agriculture and pottery were the technological innovations that spurred their success and would change the way of life for all hunter and gatherers living in Europe at that time.

Migration was not a ‘universal driver’

The research team, which included scientists from Trinity College Dublin, the University of Cambridge, and University College Dublin, noticed that the DNA from these pre-historic individuals did not have any genes from the Middle East.

Their findings instead suggest that these Baltic hunter-gatherers learned these skills through communication and cultural exchange with outsiders instead. These populations remained the same as those of the hunter-gathers throughout the Neolithic.

The study, therefore, suggests that migration was not a ‘universal driver’ of the spreading the technological innovations from the Levant, Anatolian farmers and into Europe. These technological innovations did spread throughout the Baltic region, demonstrated by archaeological findings in the region, albeit less rapidly.

The archaeological findings are very distinct to the rest of Europe, however, with a much more drawn-out and fragmentary uptake of Neolithic technologies.

Andrea Manica, one of the study’s senior authors from the University of Cambridge, said:

“Almost all ancient DNA research up to now has suggested that technologies such as agriculture spread through people migrating and settling in new areas.”

“However, in the Baltic, we find a very different picture, as there are no genetic traces of the farmers from the Levant and Anatolia who transmitted agriculture across the rest of Europe.”

“The findings suggest that indigenous hunter-gatherers adopted Neolithic ways of life through trade and contact, rather than being settled by external communities. Migrations are not the only model for technology acquisition in European prehistory.”

Slavic languages

The sequenced genomes showed no trace of Middle eastern origin but one of the Latvian samples did reveal a genetic influence from an external source traced to the Pontic Steppe in the east. It’s timing, 5-7,000 years ago, fits perfectly with previous historical linguistic research estimating the earliest Slavic languages.

There are two major theories on the spread of Indo-European languages, one that they came from Anatolia spreading across Europe with agriculture, another that they developed in the Steppes and spread at the start of the Bronze Age.

Since this new study did not reveal any farmer-related genetic input, but instead a Steppe-related component, this suggests that at least the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family possibly originated in the nomadic horse-riding peoples of the Steppe grasslands in central Asia.

The study The Neolithic Transition in the Baltic Was Not Driven by Admixture with Early European Farmers has been published in the journal Current Biology and shows that the Levantine farmers did not contribute to hunter-gatherers in the Baltic as they did in Central and Western Europe.

Reference:

Daniel G. Bradley et al. The Neolithic Transition in the Baltic Was Not Driven by Admixture with Early European Farmers. Current Biology, February 2017 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.060