Irelands population was in decline for almost 200 years before the Vikings settled in the 10th century, according to new research.

It had been assumed that the Irish population saw a steady rise across the centuries until the Famine in the 1840s, but new research at Queen’s University Belfast have produced an estimate of past population numbers which show there had been a decline for almost 200 years before the Vikings settled in Ireland in the 10th century.

The team of scientists analyzed data from the years 400 to 1200 CE and found that human activity in Ireland varied greatly during the period.

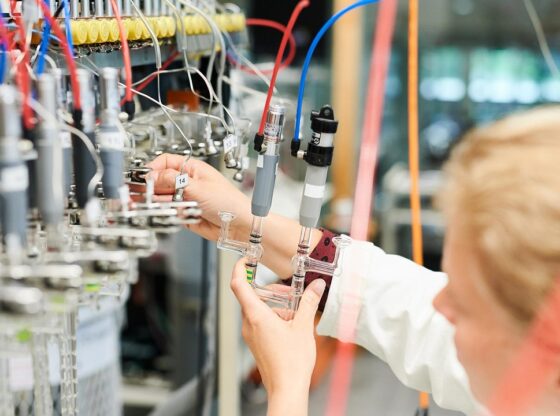

The team used proxy data to approximate population growth, they built an archaeological data science algorithm that makes use of a database on archaeological sites discovered during Ireland’s “Celtic Tiger” years (the mid-1990s to the late-2000s), when there was a boom in motorway building and other developments.

Since developers are required by law to employ archaeologists to record sites before they are destroyed. This allowed the researchers to access information that was not previously available.

The database consists of some 10,000 radiocarbon dates of human activity in Ireland, each one of these “dates” was once a living thing – a fragment of wood, a grain of cereal, or an animal or human bone. – giving the researchers a holistic understanding of human activity on the island in ancient times.

“Millions of people lived in Ireland during prehistory and the earliest Christian times.”

“Around the year 700, this population in Ireland mysteriously entered a decline, perhaps because of war, famine, plague or political unrest. However, there was no single cause or one-off event, as the decline was a gradual process.”

– Dr. Rowan McLaughlin in a university press release

The model challenges the previously held understanding that population in Ireland grew steadily until the Famine in the 1840s, indicating that the Irish population went into decline around the year 700 before the first Viking settlements came around the turn of the new millennium.

“The Vikings settled in Ireland in the tenth century, during the phase of decline and despite being few in number, they were more successful than the ‘natives’ in expanding their population. Today, genetic evidence suggests many Irish people have some Viking blood.”

– Rowan McLaughlin adds.

Recent genetic evidence has demonstrated that living Irish people share a small but significant amount of their DNA with Scandinavians, hence, the Vikings brought fresh blood to Ireland at a time when the existing population was stifled.

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin, reported in 2018, that they believe the Viking and Norman invasions of Ireland may have made a more striking impression on the DNA breakup of the country than previously thought. They discovered 23 new genetic clusters in Ireland not previously identified, leading to the belief that we may have far more Viking and Norman ancestry than previously evidenced.

This type of research is novel and new understandings may be achieved by re-imagining archaeology as a form of data science. The researchers argue that “big data” archaeology method may offer new perspectives on culture, economy, and religion: emerging via relations in economic and social networks, and that population records offer vital perspectives on past land use and how humans impact upon the environment.

“Often in archaeology, we are focused on interpreting the evidence from a single site, but analyzing quantities of data in this way allows us to think about the long term. Now we know these broad trends, we can better understand the details of everyday life.”

– Co-author Emma Hannah.

Reference:

Emma Hannah, RowanMcLaughlin Long-term archaeological perspectives on new genomic and environmental evidence from early medieval Ireland https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2019.04.001