The United States federal debt is approaching $27 trillion and is projected to rise to $78 trillion by 2028,

Debt has been a part of this country’s operations since its beginning. The U.S. government first found itself in debt in 1790, following the Revolutionary War. Since then, the debt has been fueled over the centuries by more war, economic recession, and inflation.

With the debt now approaching $27 trillion and projected to rise to $78 trillion by 2028, the size of the debt will present significant forthcoming challenges.

Some worry that excessive government debt levels can impact economic stability with ramifications for the strength of the currency in trade, economic growth, and unemployment.

How has the national debt changed during past presidential administrations? What problems are associated with a high debt load? What will the debt entail for the U.S economy in the future?

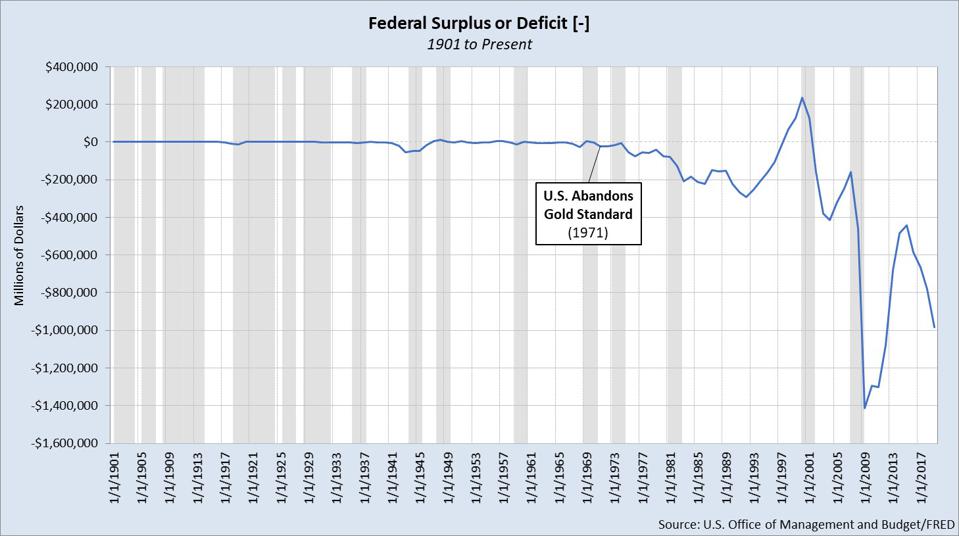

Budget Deficit

The US federal government generates a budget deficit and has been for a long time. Ever since 1971 – when President Nixon abandoned the Bretton woods system (gold standard) – the federal budget has only run a surplus in 4 out of 48 years or 8.0% of the time. The average fiscal deficit was minor before 1971 as Washington exercised greater restraint with its spending.

The US government essentially spends more money than it brings in through income-generating activities such as individual, corporate, or excise taxes. To operate in this manner of spending more than it earns, the U.S. Treasury Department issues Treasury bills, notes, and bonds. These Treasury products finance the deficit by borrowing from the investors—both domestic and foreign.

The Treasury yield on the treasury bonds is the effective interest rate that the U.S. government pays to borrow money for different lengths of time. Besides influencing how much the government pays to borrow and how much investors earn by buying government bonds, these yields also influence the interest rates that individuals and businesses pay to borrow money to buy real estate, vehicles, and equipment. Hence, the yields are of enormous importance for the overall economy which we will examine further.

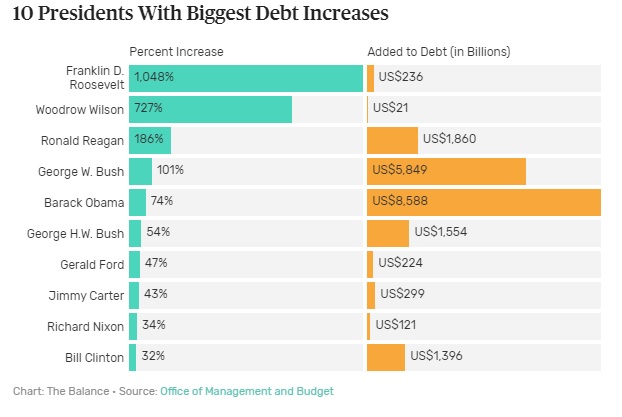

A Presidential History

The national debt in the U.S. has increased more than 21% since President Trump took office in January of 2017 with the debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratio approaching 110% in 2019. Under President Obama’s eight years, the national debt increased 100%, from $10 trillion to $20 trillion, although the economic stimulus following the 2008 financial crisis added quite a bit early on during his administration.

The debt was $669.2 billion when Jimmy Carter took office. Four years later, at the end of his term, the debt had risen to $964.5 billion. The debt increased by $1.77 trillion during Reagan’s two terms, it increased with $1.4 trillion under Bush the elder, $1.5 trillion under Clinton, $5.3 trillion under Bush the younger, $8.7 trillion during the Obama presidency and so this far $3.3 trillion under President Trump.

During World War II and its immediate aftermath, the Federal Reserve (US central bank) committed to buying as many Treasury bonds as necessary to keep yields on U.S. debt flat. The Fed may own the U.S. government bonds, but the U.S. government owns the Fed, it is hence indebted to itself. By buying up its own bonds, the U.S. financed about 15 percent of its involvement in WWII through printed dollars rather than present or future taxes.

COVID-19

Among the collateral damage of the Covid19 pandemic, the U.S. economy and the federal budget are included. The pandemic has caused an extensive economic disruption, and the government’s response has pushed the federal budget further out of balance. The U.S. government like its counterparts all over the world is spending trillions of dollars in response to the COVID-19 crisis, borrowing trillions of dollars to do so.

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, the federal debt, measured against the size of the economy, was more than twice what it was before the Great Recession and larger than it was during world war II.

The federal budget deficit is to a large extent funded by borrowing and is poised to push up against a raft of past records. The deficit accounts for about half of total federal spending (50%) so far this fiscal year and the last time borrowing made up that much of federal spending during World War II (1942 to 1945).

Similar to what the FED did during World War II, again during the Great Recession of 2007-09, it is once again poised to buy up trillions of dollars worth of U.S. Treasuries this year, covering the bulk of the anticipated $3.7 (conservative measurement) trillion deficit. And the more the Fed buys, the lower the interest rates that the government has to pay on new borrowing, and the more the U.S. Treasury can borrow overall without pushing up that interest rate.

The deficit for Fiscal Year 2020 will be at least $3.7 trillion, or 17.9% of projected GDP, and it could be even larger if Congress approves more spending increases or tax cuts in light of the pandemic. Deficits over the last 50 years have averaged just 3% of GDP. Even during the Great Recession, the largest deficit recorded (in Fiscal Year 2009) was just 9.8% of GDP.

The national debt is projected to hit $45 trillion in 2024 and $78 trillion in 2028. The US Government is deficit spending (with newly created money) at a pace never seen before in history. Due to the pandemic, the GPD is expected to decline over the next year and even with a “V” shaped recovery, research shows that high a high debt level is correlated with low economic growth which in turn decreases the foundation for which the debt can be maintained, after all, a government is only as solvent as its citizens.

A study entitled, “The Real Effects of Debt,” the Bank of International Settlements found, “At moderate levels, debt improves welfare and enhances growth. But high levels can be damaging.” The research examined data from 18 countries from 1980 to 2010. The conclusion? When government debt exceeds 85% of GDP, economic growth slows.

Debt Monetization

The FED is expanding the money supply by creating new money to buy treasures from the U.S. Government, this ‘debt monetization’ by the Federal Reserve is essentially the same as printing money. The Fed has come under criticism for “money printing,” which it did in three rounds of quantitative easing during and after the Great Recession. This came along with keeping its short-term lending rate anchored near zero for seven years.

However, the central bank’s stated aims were to bring down long-term interest rates and stimulate economic growth, not to finance the national debt.

We now know, however, that what the FED did to stimulate the economy during the financial crises was difficult to reverse in the coming decade. In December 2016, the Fed stated it would not begin the process of shrinking its balance sheet until “normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well underway”, on September 20, 2017, the Fed officially announced lift-off, the unwinding of the balance sheet was underway. The $50 billion per month taper would begin in October, and at this rate, the balance sheet was to drop below $3 trillion in 2020.

However, even before COVID 19 hit, the Fed was forced to cut rates and do QE (quantitative easing), again. The Fed’s balance sheet was expanding again since the bank began to unwind in 2017. Although the FED claimed that “These operations have no material implications for the stance of monetary policy,” according to the official FED statement, adding that there should be “little if any effect” on household and business spending nor the overall level of economic activity.

Consequences

To stave off a debt crisis, monetary policymakers create conditions that allow companies to borrow even more, increasing the potential severity of the next crisis. I.e. kicking the can down the road by even more expansionary policy, and hence avoid or delay dealing with a problem.

The Fed cannot simply keep printing money, buying government bonds, and the government can spend as much as it wants. There is only so much the government can borrow without raising interest rates and crowding out private investment. Some economists say that as long as interest rates remain low, the government can shoulder a heavier burden of debt.

The real problem with debt monetization is its effect on inflation. Inflation is a general rise in price level relative to available goods resulting in a substantial and continuing drop purchasing power in an economy over a period of time. Although another way of looking at inflation is that of currency expansion, its the classical definition, by which monetary inflation is a sustained increase in the money supply.

History has taught us that money printing leads to extremely high rates of inflation (hyperinflation), with plenty of examples, such as Weimar-era Germany, Zimbabwe in the 2007-09 period, and Venezuela currently. All three faced massive deficits that led to hyperinflation due to money printing.

At some point, if central banks create too much money, they risk an increase in inflation with too many dollars chasing too few goods – especially if the velocity of money begins to increase with the economy heating up – and they will need to raise interest rates to restrain inflation.

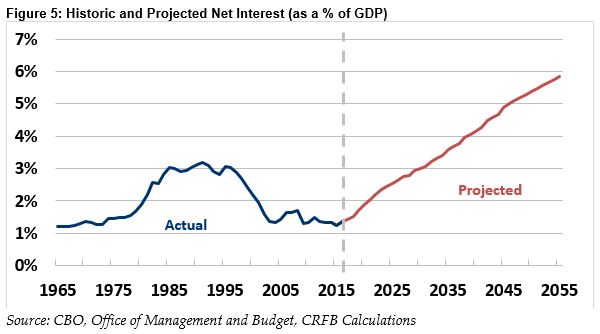

As interest rates rise, the cost of financing that debt increases along with the annual budget deficits. If interest rates rise, the government’s interest tab will go up. Raising interest rates with such a high projected future debt burden the US is actually risking default by not being able to sustain the debt load.

Even at the current low rates, the U.S government spent about $260 billion on interest in the first eight months of the fiscal year 2020, this is roughly equal to the combined spending of the Departments of Commerce, Education, Energy, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, and State.

Also, this doesn’t only pose a problem for the U.S government since when interest rates were low, companies loaded up on cheap debt. If interest rates begin to rise to offset increasing inflation, the cost of that debt on their balance sheets will become more expensive and when companies must pay more for their debt they don’t have that cash to pay workers more or buy more inventory to grow – the economy slows resulting in less income for the U.S. Government.

The Congressional Budget Office projects that deficits and the debt (as a percentage of GDP) will also rise as more Americans become eligible for Social Security and Medicare, as health care costs continue to increase faster than the economy.

There is an argument for borrowing at today’s low-interest rates so long as this borrowing is accompanied by a plan to pay down the new debt over the next few years before interest rates rise. Ultimately, however, the best way to minimize the cost of rising interest rates and prevent against interest-rate risk is to address the deficit/debt by austerity.

The federal debt simply cannot grow faster than the economy indefinitely. Eventually, if the government’s debt continues to grow this will crowd out private borrowing and interest rates will rise. At some point, action will have to be taken to rein in the deficit, but we may be a long way from that point.