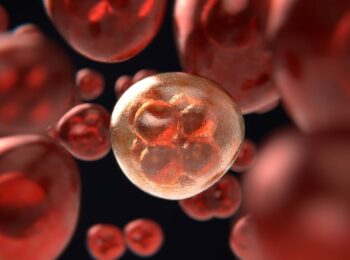

Ebola, Marburg, SARS, MERS, and now the new coronavirus Covid-19, all share one thing in common – they are thought to have originated in bats. A new study shows that internalized vaccine factories and a very special immune system are why bats are able to carry dangerous viruses without falling ill themselves.

Bats in China have been identified as one of several possible hosts for the new coronavirus Sars-CoV-2. The reason is the genetic similarity between viruses of a bat species, the Lesser horseshoe bat, and the coronavirus.

The new study conducted by researchers at UC Berkeley and other institutions found that pathogens increase in severity when they pass through a bat’s immune system, leading to the spread of virulent pathogens, including coronavirus.

Bats carry viruses without getting sick themselves, probably due to their very special immune system, in particular the lightning-fast production of a signaling molecule called interferon-alpha, which is triggered in the response of viruses. When interferon proteins are secreted by virus-infected cells, nearby cells go into a defensive, antiviral state.

This defensive antiviral state is a swift response that walls the virus out of cells. Hence, the bat’s immune system allows a virus to reproduce faster because the system’s defenses allow it to incur less harm from the virus.

This immune system may protect the bats from getting infected with high viral loads, but it also encourages these viruses to reproduce more quickly within a host before a defense can be mounted. And since the faster a virus can replicate inside a host cell, the more virulent, or severe, its results become.

This makes bats a unique reservoir of rapidly reproducing and highly transmissible viruses. While the bats can tolerate dangerous viruses, when these bat viruses then move into animals that lack a fast-response immune system, the viruses quickly overwhelm their new hosts, leading to high fatality rates.

“Some bats are able to mount this robust antiviral response, but also balance it with an anti-inflammation response,”

“Our immune system would generate widespread inflammation if attempting this same antiviral strategy. But bats appear uniquely suited to avoiding the threat of immunopathology.”

– Cara Brook, a postdoctoral Miller Fellow at UC Berkeley and the first author of the study.

“Critically, we found that bat cell lines demonstrated a signature of enhanced interferon-mediated immune response … which allowed for the establishment of rapid within-host, cell-to-cell virus transmission rates,”

– The authors explain in their study.

The rapidly replicating viruses that have evolved within bats will probably cause enhanced virulence if they jump to subsequent hosts with immune systems that diverge from those unique to bats. Whichever animal is unlucky enough to be a spillover host, it’s unlikely they’ll be ready for the fate that awaits them.

There are more than 1,400 individual species of bat, spanning almost every corner of the world and comprising around 20 percent of all mammal species. Bats have very few natural predators and live extraordinarily long in relation to their size, some bats have been found to live up to 40 years.

Reference:

Zhou P et al “Contraction of the type I IFN locus and unusual constitutive expression of IFN-α in bats.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2016. DOI: 10.1073 / pnas.1518240113.