Our DNA has mutated randomly over the millennia, and those individuals who have been best equipped for the prevailing circumstances have been able to pass their genes on. A new study sheds new light on such an advantageous adaptation – the ability to drink fresh milk.

Probably one of the more important recent adaptations for us humans concerns the ability to consume milk. Or more specifically, the ability to produce the enzyme lactase in adulthood, and thus being able to break down milk sugar. To avoid being “lactose intolerant”, which is the overwhelming state for most of the world and human history.

Tracing genes through history

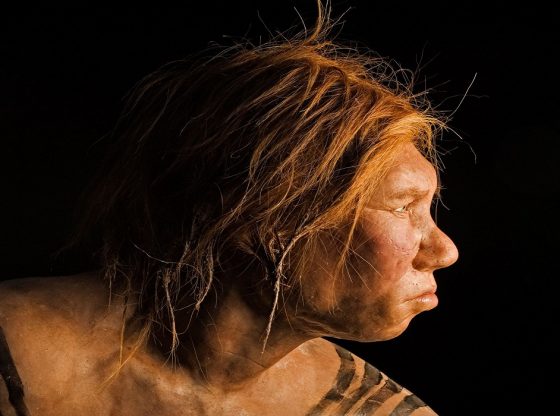

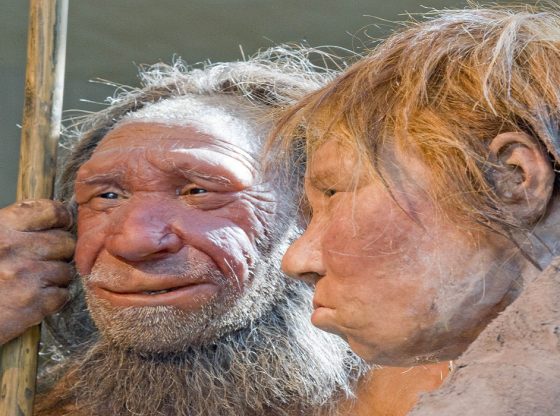

The ability has previously been traced to Europe and Northern Europe in more particular. But the first Ice Age hunters who wandered into Europe over 40,000 years ago could hardly tolerate milk. Nor are there any compelling genetic evidence indicating that Stone Age farmers tolerated fresh milk when they reached northern Europe 6,000 years ago.

Sure, Stone Age farmers milked their cows, sheep and goats for thousands of years, they probably used the milk to make butter, cheese, and sour milk. But not to drink fresh milk. Most milk-drinking adult Stone Age farmers would have suffered from stomach ache and diarrhea.

The ability to break down milk sugar as an adult seems to have become a significant survival advantage much more recently, less than two thousand years ago. The earliest secure evidence that adult Europeans are genetically equipped to be able to tolerate milk, appears about 4,200 years ago among specific groups.

This particular genetic variant to tolerate milk has thus existed at least as long. But that does not automatically imply that it was particularly common. It appears to have spread occurred much later, though, not until the Iron Age was it more widespread as it seems. As several previous studies have indicated.

New study offers greater precision

A new study by Yair Field et al. published in the journal Science has addressed this very topic with much greater precision than previous research. Aiming to answer the very question, when was it that the ability became common for us to tolerate milk in adulthood?

Yair Field and his co-authors have studied the DNA of over three thousand Britons in a project called UK10K. Their results suggest that the ability to break down milk sugar as an adult seems to have become a significant survival advantage less than two thousand years ago. But not more than one thousand years ago.

The extreme weather events of 535–536 CE

This particular study does not address the cause of this sudden spread of this genetic ability, but perhaps it was correlated with the sudden drop in temperatures in Europe around 500 CE. Caused by a volcanic eruption that led to crop failure for several seasons. Meanwhile, an epidemic of plague also rampaged across Europe.

The Byzantine historian Procopius recorded in 536 CE, in his report on the wars with the Vandals, “during this year a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness… and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear”.

Tree ring analysis by dendrochronologist Mike Baillie, of the Queen’s the University of Belfast, shows abnormally little growth in Irish oak in 536 and another sharp drop in 542, after a partial recovery.

A 2015 study by Sigl, M et al. further supported the theory of a major eruption in “535 or early 536”, with North American volcanoes considered a likely candidate. It also identified signals of the second eruption in 539-40, likely to have been in the tropics, which would have sustained the cooling effects of the first eruption through to around 550.

The event has been suggested as an explanation for the deposition of hoards of gold by Scandinavian elites at the end of the Migration Period and also to that of the decline of Teotihuacán, a huge city in Mesoamerica, with signs of civil unrest and famines.

It sounds reasonable that the ability to tolerate fresh milk became especially critical during such a difficult time, and especially in the peripheral areas of Europe where agriculture is more susceptible to change. When everyone is living on the margin, a slight advantage to tolerate milk can suddenly mean life of death.

North European traits

The British research team also found some additional genetic traits that possibly correlate to that of the ability to drink milk, spreading in the UK during the last two to three thousand years. Genes that gives light hair and blue eyes, involved in changes of the immune system and also to being particularly tall.

According to the article in Nature, although this study examined the British people, the method could be used to look at other groups, especially as more and more whole-genome data become available. The technique could shed light on whether different populations around the world are currently experiencing selection for the same traits or different ones.

For links and further reading, please see below.

References:

Yair Field, Evan A Boyle1, Natalie Telis,Ziyue Gao1, Kyle J. Gaulton1, David Golan1, Loic Yengo, Ghislain Rocheleau, Philippe Frogue, Mark I. McCarthy, Jonathan K. Pritchard, Detection of human adaptation during the past 2000 years

M. Sigl, M. Winstrup, J. R. McConnell, K. C. Welten, et al Timing and climate forcing of volcanic eruptions for the past 2,500 years

Nature: Scientists track last 2,000 years of British evolution